- Home

- C. Sean McGee

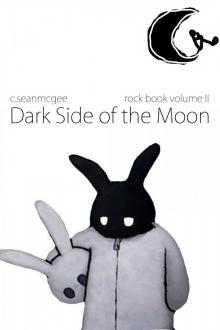

Dark Side of the Moon by C. Sean McGee

Dark Side of the Moon by C. Sean McGee Read online

ROCK BOOK VOLUME II

DARK SIDE OF THE MOON

BY

C. SEAN MCGEE

Rock Book Volume II: Dark Side of the Moon

Copyright© 2013 Cian Sean McGee

CSM Publishing

‘The Free Art Collection’

Santo André, Sao Paulo, Brazil

First Edition

All rights reserved. This FREE ART ebook may be copied, distributed, reposted, reprinted and shared, provided it appears in its entirety without alteration, the reader is not charged to access it and the downloader or sharer does not attempt to assume any part of the work as their own.

Free art, just a writer’s voice and your conscious ear.

Cover Design: C. Sean McGee

Moon Man Image: Carol Ribeiro

Interior layout: C. Sean McGee

Author Photo: Carla Raiter

Disclaimer:

This book is an homage to the works of Pink Floyd and notably Dark Side of the Moon. This is a literary cover. Lyrics from the album are used throughout the story and I hope you kind people don’t sue me for it. It is meant as a celebration of a great piece of music celebrated in unique way, through story.

CHAPTERS

SPEAK TO ME

BREATHE

ON THE RUN

TIME

THE GREAT GIG IN THE SKY

MONEY

US AND THEM

ANY COLOUR YOU LIKE

BRAIN DAMAGE

ECLIPSE

FOR KELI, NENAGH AND TOMÁS

SPEAK TO ME

When a heart beats inside of a rabbit, one can assume that even in his stillness, even in the absence of his breath or in the muting of his cry, even in the coldness of his skin or in the vacuity of his eye, that he is, in some way, alive and if you asked him then maybe he might tell you that this was how it had always seemed in that, at no point; in all that he had seen and all that he had done and in all the fields unto which all he had run, had ever he felt like life had, in any way, already begun.

Theodore’s heart thumped over and over and he followed each beat like a print in time, wondering if he was walking in slow circles towards his own intrepid finality and he saw himself in a bright orange field with hundreds of thousands of millions of bright orange flowers all swaying about under a bright orange sun which had been painted upon a bright blue sky and with every beat of his heart, a giant mechanical fist swung down from the bright invisible heavens and crushed a circle of bright orange flowers not far from where he stood and as he hopped along through the long leaves of grass; feeling the sun warming his fine fur as the bright orange flowers gently brushed his face, tickling the skin by his bushy tail, he wondered to himself, “Am I mad?”

And spurred by his yearning, to be not insane, Theodore the rabbit wished gone of the sun and prayed for deplorable rain.

“He killed himself” he said out loud in his head as if the words were another’s describing how this rabbit had wound up so obviously dead.

“He’s crazy.”

“He’s mad.”

“He’s bonkers.”

“Confused.”

“He’ll never win a race with apathetic shoes.”

“He’s loopy.”

“He’s balmy.”

“He’s clearly insane”

“There’s obviously something defunct in his brain.”

And the voices repeated inside of his mind and he wished in the colour for a safe place to hide; in the greens of the grass and orange of flowers, for somewhere to burrow, a covert to cower.

And the sound of his beating heart was now pounding faster and louder and it didn’t seem like any of it was ever going to end. And with every perorated thump, he stood in vacant awe as above him, through the bright blue sky came a massive crushing mechanical hammer like fist and it stretched out from the heavens and beat down on the ground with each beat of his heart a then torturous sound; pulverising, evulsing, defiling, expulsing each bright orange flower so all that was left was a cavernous breach in the earth, a colourless turn of affection, black fetid dirt.

Theodore hopped through the blades of grass and the coloured flowers trying to forget the sound of his own heart but it was no use. For every orange flower that touched his little pink nose, a thousand more were trampled by massive swinging mechanical fists until the whole plain was swiftly raped of the entire of its colour and Theodore stood; with his little pink nose sniffing into the air, by the last blade of grass that clung like a frightened child to the last orange flower which craned its neck towards the heavens in a last defiant kiss of the sun.

Looking up into the blue sky, Theodore could see the shiny silver mechanical fist gently swaying back and forth as if some fine thread were keeping it bridged to the stars and only the finest breath would set it free, crushing down upon him.

And so he held of his breath and tried to still his despotic heart and his ears filled with heavied influence from the drunken banter of stupid rabbits and then the sound of locks clicking and pockets picking and the ka-ching of the cash registers ringing like a chorus line singing that everything thought was everything told and everything taught was everything sold and each thing had a price and each price had a place and each place had a number and each number had a face and each lie could be gauged as a scholarly truth just as time unto money or age unto youth, for one and the other were thought of as real, as states to acquire or penchants to steal and the sound of it all was so loud in his head that poor old Theodore, he wished and wished he were dead.

He turned of his sight from the high in the sky and he spoke to the flower with a tear in his eye and he said “I am sorry, it is who that I am, that I imagined you flower and that mechanical hand and I shouldn’t have ever, imagined you alive, for all I have done is to curse you to die.”

And the flower she craned with a smile and a sigh and she wiped with her petal of the winter in his eye.

“I’m not crazy” Theodore said.

The flower smiled.

Theodore looked up into the sky and he could see, riding on the mechanical fist was a small angry looking black and white striped bigot and he was screaming and drunk and he reeked and he stunk and his words they were sinking, defeating and sunk.

“You’ve always been mad, like most of us have, very hard to explain why you’re not mad” said The Badger with a moment’s contemplation in a moment of hesitation, “even if you’re not mad.”

Theodore kissed the bright orange flower and his heart beat one last time and as he looked up into the bright blue sky where the bright orange sun played witness to the life and death of each and everyone one, he smiled and hoped that this would be some kind of an end.

BREATHE

“Do you still see him? Is he with you, in this room?” asked The Guru.

The sound of tortured laughing and selling hands closed out in his mind as he opened his eyes and saw a small smiling monkey in comfortable sweat pants and a green and white striped turtle neck sweater standing above him as he lay on his back staring up at an image of orange flowers painted onto the ceiling of a room with brightly coloured walls; bright blue to be exact and he, lying on a white leather couch and it looked as if he were floating on a cloud looking down at the world that haunted his mind and seeing; just as The Guru had said, that he was in fact not there, that he was, above and beyond all moony transitions and that the swinging fist that haunted his imagination was merely his own reflections, caught in the breaking of wave.

Theodore looked around the room seeing colour in everything but with his caliginous eyes, finding only the grey smudges and flickers of black and white where small threads of fabric had wound a

way like escaping screws from the corners of chairs and the tiny scratches in the paint around the handle of the door where probably an aardvark or a ferret had accidentally brushed its claws when reaching for the poorly shaped handle.

This bothered him.

“Well?” asked The Guru.

Theodore turned his head around to the expanse of colour and accepted that they were in fact without disrupting company, just he and The Guru, alone in the theatre of self-help.

“I can’t see him, no” said Theodore. “But that doesn’t mean his isn’t there.”

“Is that what you think? That you’re mysterious Badger is hiding under the sofa, behind the blinds maybe, behind my chair even.”

“You wouldn’t get it” said Theodore.

“Well then help me. This is what this is all about, to learn how to help ourselves so that we can help others. So help me, if he’s not hiding in this room then where is he hiding?”

“Inside me” said Theodore.

The Guru made some scribbles and notes on the paper in his hands but Theodore paid no mind. He had once concerned himself with these notes like most of The Burrowers had and still did, wanting so much for everything that he said to sound agreeable and poignant and usually the scratching of pen on paper would bring about some shrill of worry within all of the animals who laid upon this white couch but today; for Theodore, the scratching of sharpened lead on paper sounded no different to his own nails against the coarse sand out in the pits and just as his work ages his expectation and saddled his zest, so too he assumed, must the work of this brightly coloured monkey.

“Are you happy? It’s ok if you’re not. We all get sad you know. We all feel like we could be doing something different, our ears could be longer, our tail bushier, our nose a little pinker.”

“You do hear yourself? You just described a rabbit and you said we” said Theodore.

“I guess I did” said The Guru laughing to himself.

“And you see how that makes no sense then… because you’re a monkey.”

“It’s a metaphor Theodore.”

“Why are we here?”

“On the moon? That’s a very deep question, a very good question indeed. Why do you think we’re here?”

“Is it a good question? Is it, really? It just seems so lazy you know, asking you for the answer instead of finding out for myself. Do you have the answer? Do you know anything at all?”

“You seem sad Theodore. Is your work not satisfying anymore? And sex, how is the sex?”

“See that’s the thing. I know who I am, I know what I am. I know what I’m supposed to do and I know what I’m supposed to like. I see everyone else doing it and liking it, it’s just, I don’t know…”

“I want you to look in this mirror for me.”

Theodore hopped off the couch and over to the far end of the room where the monkey was standing by what was for him an average mirror but for Theodore; a tiny white fluffy bunny, was in fact tremendous in its height, like catching one’s reflection at the foot of a glacier.

“I want you to look into your eyes, into the inner you, the true Theodore and I want you to speak to that Theodore. I want you to say. I am Theodore, I am me, I love me and I am special. I love myself and I love being me. I am important and the things I do and say make a difference. Hurray for me, hurray, hurray, hurray.”

Theodore did as The Guru asked, looking himself long in the mirror and seeing his reflection but seeing it not as he had once seen himself, seeing it older, like a face you just can’t put a name to. And he seemed lost, looking into his own red eyes. He wondered; in the instant before he spoke, whether he would ever be able to find himself lost in a crowd, were it that he had found himself separated from his own self.

He said the words the way he was supposed to say them but the sound was strange and their feeling had no effect. Being a burrowing rabbit was so much different to being any other kind of rabbit and for Theodore, being a rabbit of his own making; being Theodore, was so much different to just being a conventional rabbit and he was having such a hard time at doing just that, being just like everyone else and being happy about it.

“You know I had a dog in here earlier on with the same problem. He wasn’t happy either. He wanted to be like a monkey, can you believe that? And he’s a canine. But it goes to show you that you’re not alone, everyone has these same thoughts from time to time. We all think of ourselves differently than we truly are. And we’re all the same, we’re all special. We’re all important and that’s what matters” said The Guru.

Theodore gazed into his own reflection watching his pupils swell and recede like a black conspiring tide and he wondered if when other rabbits looked into his eyes, could they see his doubt and would they see him, as in how he felt?

Different, as in, not a rabbit.

“Honestly Theodore, I believe there is nothing wrong with you at all. You’re a health young rabbit. Tell me, how many times per day are you having sex?”

“Sorry?” asked Theodore.

“Sex Theodore, how many times per day are you, you know?” asked The Guru, thrusting his hips back and forth.

Theodore looked droll in the application of his humour. His tired eyes blinked once or twice before he finally gave a slow response.

“Maybe thirty times per day. I mean, that’s normal I guess, isn’t it?”

“Hey, who’s to say what’s normal? We don’t use that word around here. It’s not in my vocabulary. There’s no normal or expected or problem or right or wrong, everyone is unique and special here. But for a rabbit of your age, normal is anywhere from fifty to maybe a hundred times per day.”

“I thought you said normal was not in your vocabulary?”

“Oh no I was just showing like a comparison of for example more traditional ways of exploring a problem like this whereas I treat a problem like this looking not at the problem itself but maybe, in the environment, what might be causing the problem.”

“Can I go?”

“But we’re not done. I still had some photos of sad rabbits saying depressive sentiments. It was going to be next and…”

“I’d really like to get back to work. I’m ok, really I am. Look, I’m happy, see” he said, wearing a limber oversized smile like a young child would, their father’s coat.

“You know life is like a…”

“A what?” asked Theodore.

“Oh where is it?”

“What did you lose?”

“I had a card here. It was a white card. It had all my closing proverbs. I left it right here. You didn’t see it did you?”

“No I didn’t. But that’s ok. Maybe next time.”

“No it’s not ok. There’s a science to this. You’re supposed to finish on a life quote. I have to conclude the session.”

“Well, can’t you just give me one off your head or something?”

“I don’t have one off the top of my head. I keep them on the white card. That’s what the white card is for but my stupid receptionist. Ugh, she angers me sometimes. She just moves things about like it’s her place.”

“Relax Guru, it’s fine. I don’t think life really offers any real conclusions anyway, not the kind we’re hoping or expecting.”

“Just give me a second. The quote is great. It’s about life and everything being in balance and… it’s here somewhere, I know it” said The Guru.

“Listen, I’m feeling kind of randy so I might go and have some sex now but later, when you find it, you can read me that quote, deal?”

“Sure, yeah that’s a good idea, deal. Hey, have great sex.”

Theodore stepped on a small button by the right of the door and the small button pressed down and the lock clicked and the door paused open and Theodore hopped out into the hallway and headed off back along through the winding corridors passing hundreds of unmarked doors on his way back into the tunnels to continue his work.

“Theodore” yelled The Guru down the corridor.

Theodore sto

pped and turned his little bunny head.

“Breathe” he shouted.

“What?” yelled Theodore.

“Breathe in the air” The Guru shouted. “When it gets heavy and you’re thinking old in your mind and you feel long in your step, remember to breathe, nothing else, just breathe in the air. And yoga. Do your yoga. It will even out your soul. More yoga, ok? Oh and hey, you’re special and I love you.”

“Ok” said Theodore dryly.

“Oh, and don’t be afraid to care. The things you love, they won’t leave you, not if you love them and you love yourself enough for them to want to stay. Breathe, Theodore, just breathe” shouted The Guru.

Theodore turned away again and hopped off down the hallway and waited by a large sign of a burrowing rabbit by a large metal track. On his way, he caught the eye of a raggedy but pretty rabbit looking at him with strange affection. And it could have been hunger in her eye or it could have something entirely else and as he hopped past, he looked in her direction as he did every time he passed her stop and he wished he could have done something other than pretend that he hadn’t see her stare.

What a stupid rabbit thing to do.

Beside him; spaced generously, where many more signs stretched out the length of the track before him and each sign housed a different animal; some large some large and some insectually small.

Before each sign stood the animal or insect that was no different as the image itself and all of the animals huddled together and they bickered and they shoved and they pushed one another around, desperately vying to be first to board the afternoon train.

Along the line of the track, waiting for the first carriage down to the last was the order in which the animals were needed, respected and unto the moon, gave their service. The dogs were first, taking the most comfortable of the carriages and the least labour of the work. It had been better, according to the monkeys, to give passage and right to the dogs so that they wouldn’t eat and make bloodied toys out of all the smaller and more functional animals. The dogs did very little, so better then that the little they did be somewhere upon where there very little did no harm.

Coffee and Sugar

Coffee and Sugar Happy People Live Here

Happy People Live Here_preview.jpg) Alex and The Gruff (A Tale of Horror)

Alex and The Gruff (A Tale of Horror) Dark Side of the Moon

Dark Side of the Moon The Terror{blist}

The Terror{blist}_preview.jpg) The Anarchist (...Or About How Everything I Own Is Covered In A Fine Red Dust)

The Anarchist (...Or About How Everything I Own Is Covered In A Fine Red Dust) A Rising Fall

A Rising Fall Heaven is Full of Arseholes

Heaven is Full of Arseholes Utopian Circus

Utopian Circus![[2014] The Time Traveler's Wife Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/2014_the_time_travelers_wife_preview.jpg) [2014] The Time Traveler's Wife

[2014] The Time Traveler's Wife London When it Rains

London When it Rains Dark Side of the Moon by C. Sean McGee

Dark Side of the Moon by C. Sean McGee![The Terror[blist] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/06/the_terrorblist_preview.jpg) The Terror[blist]

The Terror[blist]